I was very sad to hear that Sir Clive Sinclair, the British inventor and pioneer of home computing, passed away yesterday at the age of 81. Apparently he’d been battling cancer for some years.

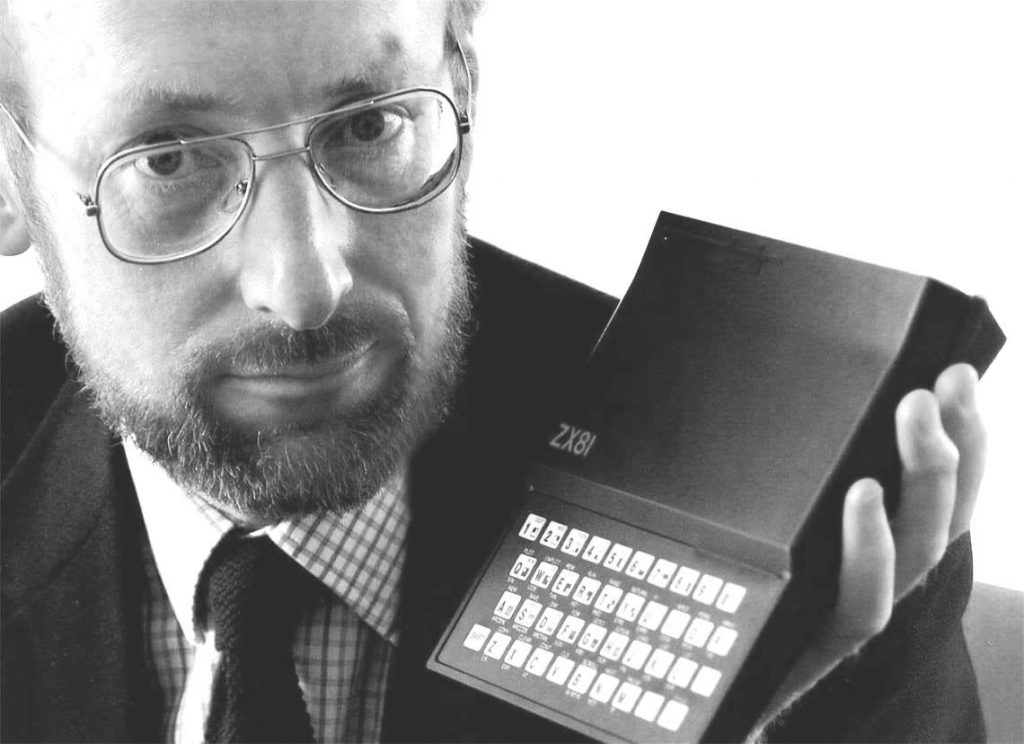

Sinclair is widely credited as being the man who made computers popular and affordable, bringing them into millions of British homes. He did this after inventing pocket calculators, tiny radios and TVs, and selling a range of hifi amps and scientific instruments. The ZX80, ZX81 and ZX Spectrum sold in vast quantities, not because they were particularly good computers, but because they hit a perfect balance of performance and price, and caught the public’s imagination at an interesting point in Britain’s history. Traditional heavy industries were declining fast, and all of a sudden we seemed to be very good at the exciting new stuff.

Helped by the government-backed BBC Computer Literacy Programme, my generation was among the first to be brought up with computers, and they appeared in schools from when I was about eight years old. The very first computer I ever saw working, and got to use, was a Commodore PET, which belonged to one of the teachers at my school. Shortly after, the school acquired a BBC Micro, but in homes the length and breadth of Britain, cheaper Sinclair machines dominated the scene. I got a ZX81 for my ninth birthday, and a Spectrum +2 a few years later.

I was never quite as much of a computer nerd as many of my friends, but it was impossible not to get caught up in the tidal wave of excitement that these simple home computers brought with them. It was the beginning of the digital revolution that created today’s information-based society and economy, and being there at the start is something I remember fondly.

Unfortunately, Clive Sinclair wasn’t the best businessman in the world, and his failures probably outnumber his successes. Sinclair Research ran into serious problems after the farcical, premature launch of the QL computer and the commercial failure of the C5 electric trike (which was, undoubtedly, a brilliant idea 30 years ahead of its time). Eventually, he was forced to sell his computer designs and brand to Amstrad, who kept the Spectrum going for a few years longer with upgraded designs.

Although Clive Sinclair faded from the limelight around this time, he kept researching and developing new ideas, although they tended to be things that didn’t capture the public’s imagination in the same way as his ZX range did. He did, however, have a last stab at computing in the late eighties, launching a machine called the Z88, made and sold by Cambridge Computer (Amstrad had the sole rights to the Sinclair brand by this time). I didn’t own one at the time, but I have one now. It’s a typically quirky and idiosyncratic machine with some frustrating limitations, but it was the first properly affordable and viable portable computer, coming years before laptops were common and even remotely within reach of ordinary people. After that, though, Sinclair never produced another computer again, which is a real shame. Later in his life, Sinclair stated in an interview that he didn’t use the internet or computers at all, which must have taken a few people by surprise, given that he was responsible for putting computers into millions of living rooms, and changing them from mysterious, scary things into friendly consumer products.

Sinclair had a reputation for being a difficult man to know and work with, prone to angry outbursts, and with a single-mindedness that blinded him to mistakes he was making. It’s always struck me as being sad that he managed to make and lose a fortune in his lifetime, and after achieving enormous success in the first half of his life, he became something of a laughing stock in the second half. That said, I think his life is a thing worth celebrating, as he was clearly a gifted and visionary man who is as worthy of recognition and appreciation as Alan Turing, Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. The legacy of Sinclair’s products is an incredible one – the ZX range spawned an entire industry to provide hardware and software for the new machines, and IT careers were forged as kids the world over learned how to code in their bedrooms. Legendary video game creators cut their teeth developing hits for the Spectrum. Linus Torvalds wrote the first version of Linux on a Sinclair QL.

I own three Sinclair computers (ZX81, Spectrum and Z88) and I’m enormously fond of them. Sinclair could create things that were far more than the sum of their parts, pushing components to their limits and using clever design tricks to keep things simple and cheap. No-one else quite managed to match his ability to innovate and put things in peoples’ hands in such an effective and friendly way. The cultural impact of Sinclair’s home micro revolution was incredible, and many of us have very fond memories of it all many decades later.

So, farewell, Uncle Clive, and thanks for everything. They say you should never meet your heroes, and it’s possibly just as well I never did meet him, as I probably would have been disappointed, but I remain grateful for the little black boxes he created, and the possibilities they brought into our lives.

I’ll leave you with Micro Men, the 2009 BBC drama about Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry, and the early days of home computing. The historical accuracy is questionable in places, but the excitement of the era is brilliantly captured, and it’s well worth a watch.

Sir Clive Sinclair, 30th July 1940 to 16th September 2021